Partners vs. Strangers: Identification of the Group Membership in the Contribution to Public Goods

Main Article Content

Keywords

Public Goods Game, Contribution, Free-rider, Learning

Abstract

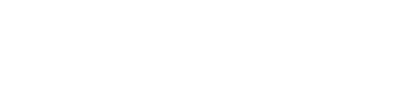

This paper studies the effect of experience, the inter-temporal strategy and the group size as the possible explanations to the highest levels of contribution to equilibrium in a game of public goods. All these variables together allow capturing the effect of the group membership; keeping in mind that the more information collected about its members' behavior, the greater the levels of contribution. Therefore, treatment was implemented in which subjects interact in a group with permanent members (partners), and other treatment where the group changes randomly in each round (strangers). In addition, crossed treatments were carried out, in which first stage partners or strangers’ status is surprisingly changed in the second stage of the experiment. Groups of four or five members were considered to analyze the effect of the group size. Results show that the average contribution is positive and gradually converges to the Nash equilibrium as repetitions increase. Although there is evidence in favor of the intertemporal strategy, it critically depends on the stability of the group's composition. Regarding the group size, four-member groups show a higher average contribution.

Downloads

References

Andreoni, J. (1995a). Cooperation in public-goods experiments: kindness or confusion? The American Economic Review, 85(4), 891-904.

Andreoni, J. (1995b). Warm-glow versus cold-prickle: the effects of positive and negative framing on cooperation in experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(1), 1-21.

Andreoni, J. y Croson, R. (1998). Partner versus stranger: Ramdom Rematching in Public Goods Experiments. En C. Plott y V. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, pp. 776-83.

Brandts, J.; Saijo, T. y Schram, A. (2004). How universal is behavior? A four country comparison of spite and cooperation in voluntary contribution mechanisms. Public Choice, 119(3-4), 381-424.

Cárdenas, J. C. (2004). Regulaciones y normas en lo público y lo colectivo: exploraciones desde el laboratorio económico. Documentos CEDE, 7191, 1-31.

Chaudhuri, A. (2010). Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Experimental Economics, 14(1), 47-83.

Croson, R. (1996). Partners and strangers revisited. Economics Letters, 53(1), 25-32.

Falkinger, J.; Fehr, E.; Gächter, S. y Winter-Ebmer, R. (2000). A simple mechanism for the efficient provision of public goods: Experimental evidence. The American Economic Review, 90(1), 247-64.

Fatas, E. y Roig, J. (2004). Equidad y evasión fiscal. Un test experimental. Revista de Economía Aplicada, 12(34), 17-37.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171-78.

Gächter, S. y Thöni, C. (2005). Social learning and voluntary cooperation among like-minded people. Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2), 303-14.

Goeree, J.; Holt, C. y Laury, S. (2002). Private costs and public benefits: unraveling the effects of altruism and noisy behavior. Journal of Public Economics, 83(2), 255-76.

Gutiérrez, J. (2008). Mecanismos de contribución voluntaria en un sistema de recaudación de impuestos: un análisis experimental. Revista CIFE, 13, 264-86.

Halevy, N.; Weisel, O. y Bornstein, G. (2011). “In-group love” and “Out-group hate” in repeated interaction between groups. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. Recuperado de http://www.econ.mpg.de/files/2012/staff/Weisel_JBDM_2011.pdf

Isaac, M. y Walker, J. (1988). Group size effects in public goods provision: The voluntary contributions mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103(1), 179-99.

Jamal, K. y Sunder, S. (1991). Money vs gaming: Effects of salient monetary payments in double oral auctions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 49(1), 151-66.

Ledyard, J. (1994). Public goods: A survey of experimental research. En J. Kagel y A. Roth (Eds.), Handbook of Experimental Economics, Princeton University Press.

Marwell, G. y Ames, R. (1979). Experiments on the provision of public goods. I. Resources, interest, group size, and the free-rider problem. American Journal of Sociology, 84(6), 1335-60.

Melo, L. (1993). Los incentivos monetarios en la economía experimental: un estudio de caso. Desarrollo y Sociedad, 31, 91-120.

Ockenfels, A. y Weimann, J. (1999). Types and patterns: an experimental East-West-German comparison of cooperation and solidarity. Journal of Public Economics, 71(2), 275-87.

Palfrey, T. y Prisbrey, J. (1997). Anomalous behavior in public goods experiments: How much and why? The American Economic Review, 87(5), 829-46.

Read, D. (2005). Monetary incentives, what are they good for? Journal of Economic Methodology, 12(2), 265-76.

Roth, A. (1995). Introduction to experimental economics. En J. Kagel y A. Roth (Eds.), Handbook of Experimental Economics (pp. 3-110). Princeton University Press.

Solow, J. y Kirkwood, N. (2002). Group identity and gender in public goods experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 48, 403-12.

Villion, J. (2010). L’Economie expérimentale. Idées, 161. Recuperado de http://www2.cndp. fr/archivage/valid/71817/71817-11123-14180.pdf

Zelmer, J. (2003). Linear public goods experiments: A meta-analysis. Experimental Economics, 6(3), 299-310.